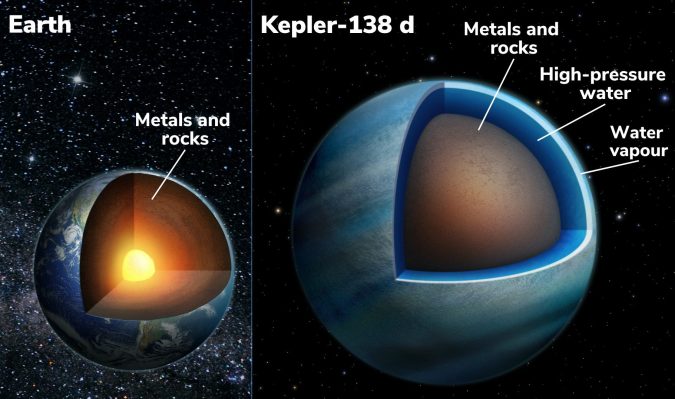

Two planets that were originally discovered by the Kepler mission may not be what we thought they were. Based on an initial characterization, it was thought these planets were rocky bodies a bit larger than Earth. But continued observation has produced data that indicates the planets are much less dense than we originally thought. And the only realistic way to get the sort of densities they now seem to have is for a substantial amount of their volume to be occupied by water or a similar fluid.

We do have bodies like this in our Solar System—most notably the moon Europa, which has a rocky core surrounded by a watery shell capped by ice. But these new planets are much closer to their host star, which means their surfaces are probably a blurry boundary between a vast ocean and a steam-filled atmosphere.

Let’s revisit that

There are two main methods for finding an exoplanet. One is to watch for dips in the light from their star, caused by planets with an orbit that takes them between the star and Earth. The second is to track whether the star’s light periodically shifts to redder or bluer wavelengths, caused by the star moving due to the gravitational pull of orbiting planets.

Either of those methods can tell us whether or not a planet is present. But having both gives us a lot of information about the planet. The amount of light blocked by the planet can give us an estimate of its size. The amount of red- and blue-shifting of the star’s light can indicate the planet’s mass. With both of those, we can find out its density. And density limits what sorts of materials it can be composed of—low density means rich in gas, high density means rocky with a metal-rich core.

That’s exactly what we were able to do at the Kepler-138 system. Data from both these methods suggested that the system contains three planets. Kepler-138b appears to be a small, Mars-sized rocky body. Kepler-138c and Kepler-138d both fell into the category of super-Earths: rocky planets that were somewhat larger than Earth and considerably more massive. All of them orbited quite close to Kepler-138a, a red dwarf star, with the most distant (Kepler-138d) orbiting at 0.15 astronomical units (an AU is the typical distance between Earth and the Sun).

In the grand scheme of things, there was nothing unusual about this system that would demand a second look. But researchers thought that it made a good candidate for studies of the planet’s atmospheres. While the planet will block all light as it transits in front of its host star, a small amount of light will pass through the atmosphere on its way to Earth. And the molecules in that atmosphere will absorb some specific wavelengths, allowing us to discern their presence.

To perform that study, a team of researchers obtained data from the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes, timed for when Kepler-138d was transiting in front of the star. And that’s when things started to get weird.

Revisions upon revisions

With three planets packed into a small area near the red dwarf, they’re close enough to each other that they can influence their orbits. These create what are called “transit timing variations,” meaning that a planet doesn’t show up in front of its host start at exactly the time its orbit would normally take it there. For example, one of the planets might be in a position where its gravitational pull will slow down another, causing its transit to start a bit later than calculations might otherwise suggest.

This can provide limits for planet mass estimates, as well, so precise measurements of transit timing variations are good to have. And, because the Hubble and Spitzer observations came quite a while after the Kepler data, it meant that we could calculate variations across a seven-year span.

As it turned out, however, we couldn’t. If you estimated the masses based on Kepler measurements and then tried to use that to predict the transits in later measurements, you’d fail. In fact, everything was messed up. “No three-planet model can simultaneously reproduce the Kepler, HST, and Spitzer transit times of Kepler-138 d,” the researchers conclude.

That probably seems awkward. But if a three-planet model failed, the researchers had an obvious backup: trying a four-planet model instead. And that managed to make sense of the data. It also provided an estimate of the fourth planet’s location and mass: about half the size of Earth, orbiting roughly 0.2 astronomical units from the star. The planet, Kepler-138e, doesn’t appear to transit in front of the host star, so its presence hasn’t been confirmed yet.

Assuming it’s accurate, however, the presence of Kepler-138e has consequences. It would also be exerting a gravitational pull on the star, which would contribute to all the red and blue shifts in the star’s light that were used to determine the mass of the other planets. So all of the mass estimates based on the earlier data had to be completely revised in light of the presence of another planet. And things continued to get weird when that was done.

Water, water, everywhere

The two larger planets, Kepler-138c and Kepler-138d, were originally thought to be quite different: both rocky but with metal cores that differed greatly in size. With the revised measurements, however, they were essentially twins. And they were considerably less dense than the earlier estimates.

One way for that to work is if they have a large, hydrogen-rich atmosphere. But the planets are so close to their host star that this isn’t a viable option; radiation from the star is intense enough that the atmosphere would be stripped away within 50 million years, and the system is estimated to be over a billion years old.

An alternative is a planet rich in what are called volatiles, things like water or ammonia that can be found as gases, ices, and liquids under the conditions found in different parts of the Solar System. While a number of potential chemicals could account for the planets’ density, the researchers think in terms of water since there are several water-rich worlds in our Solar System, most notably Jupiter’s moon, Europa.

Matching the density of the two planets produces a model that has a bit over 10 percent of the planet’s mass composed of water. This, however, means that about half the planet’s volume is water. While some of that might be incorporated into the rocky core, it likely means a planet-wide ocean that’s kilometers deep. And, unlike the icy moons, the planet is close enough that much of the water would be liquid, and the atmosphere would be filled with water vapor. Due to the planet’s mass, the pressure of the atmosphere would be immense and could create a layer of supercritical water between the atmosphere and the ocean.

The water-filled moons of the outer Solar System are easy to explain, because they formed in a region where water would exist as ice, and thus could condense onto smaller bodies that merged to form the moons. But these planets are orbiting in an area where water is either liquid or, more likely, remains gaseous. How could they possibly form?

The researchers suggest that the orbital periods of the planets provide a clue. They are in resonance, meaning that the ratios of their orbital period can be expressed as a ratio of two single-digit numbers (i.e., 5:3). Resonant orbits are considered stable, as the regular gravitational interactions among the planets keep them from getting out of alignment. So the researchers suggest that the planets likely formed in an area of their exosolar system where ice predominated and then migrated inward toward the star until the resonance stabilized their orbits and stopped the migration.

Obviously, given that we haven’t confirmed that a fourth planet exists, there’s a lot here that needs to be verified before we can be comfortable saying we’ve definitely found water worlds. But even in its current tentative state, the results suggest that there’s still a lot of potential for new findings in places where the data seemed to point to a rather run-of-the-mill collection of planets. Given that Kepler identified thousands of exosolar systems like that, there seems to be immense potential for revisiting data and looking for surprises.

Nature Astronomy, 2022. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-022-01835-4 (About DOIs).

Suggest an edit to this article

Check out our new Discord Cyber Awareness Server. Stay informed with CVE Alerts, Cybersecurity News & More!

Remember, CyberSecurity Starts With You!

- Globally, 30,000 websites are hacked daily.

- 64% of companies worldwide have experienced at least one form of a cyber attack.

- There were 20M breached records in March 2021.

- In 2020, ransomware cases grew by 150%.

- Email is responsible for around 94% of all malware.

- Every 39 seconds, there is a new attack somewhere on the web.

- An average of around 24,000 malicious mobile apps are blocked daily on the internet.